Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts, Day of the Dead, Oct.-Nov. 2014, Interactive installation

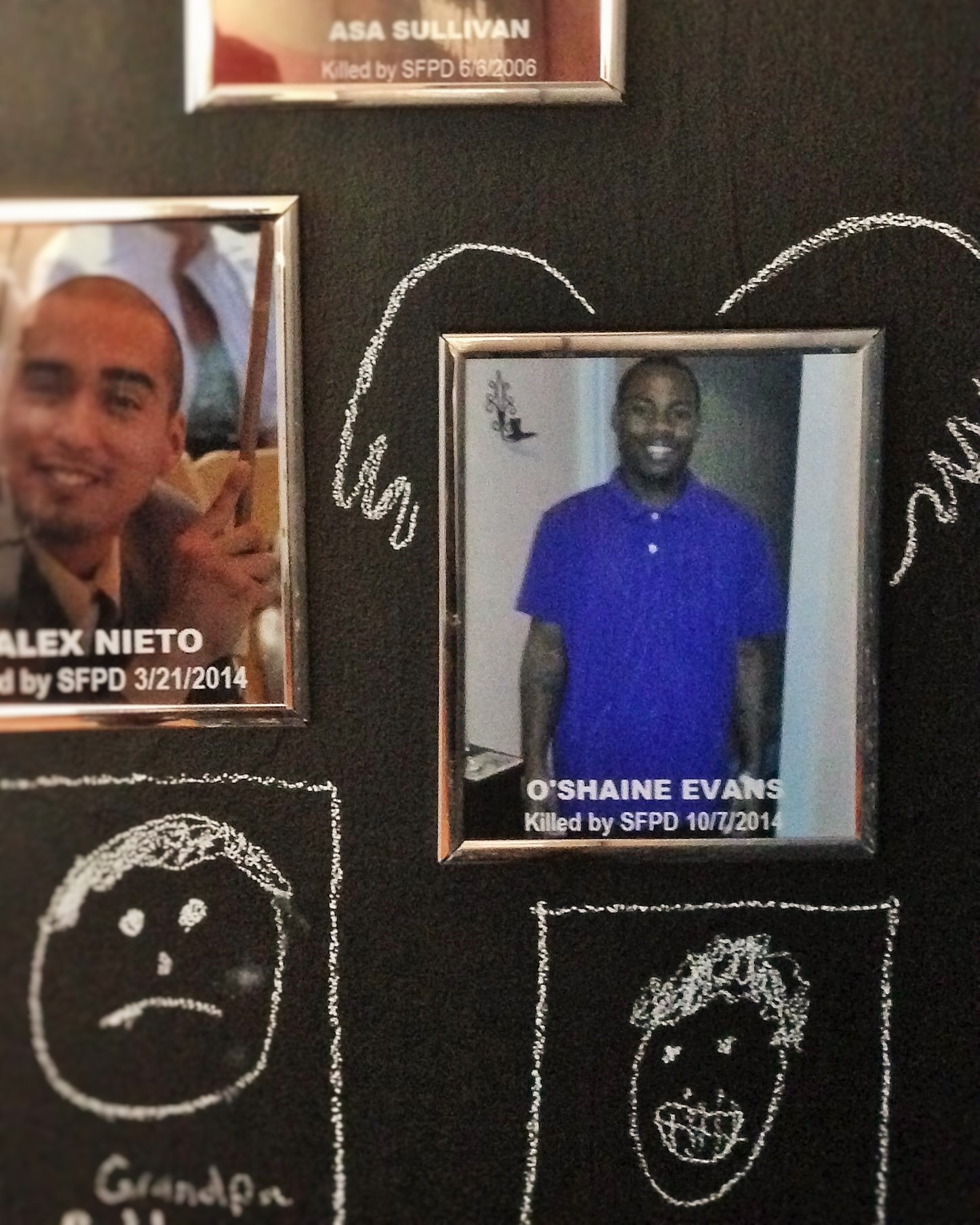

Over the extended Columbus Day weekend (October 11th-13th), we began readying the walls of another altar. Our altar at the Mission Cultural Center for Latino Arts is titled “Unaccountable Murders: Counting and recounting homicides by police in San Francisco,” a collaboration of filmmaker Ivonne Iriondo, activist and artist Erin McElroy, and myself. Erin McElroy is best known for her work with the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project (AEMP), which gained notoriety for mapping out the escalating crisis of Ellis Act Evictions. However, after Alex Nieto was killed March 21, 2014, the AEMP felt compelled to map out known fatal officer-involved shootings since 1985 in San Francisco.

For many, the death of Alex Nieto was a “death by gentrification,” because the police was called to the hill by an unnamed dogwalker, who many suspect to be a techie newcomer to the neighborhood. Many suspect that Alex was profiled as dangerous simply for being working-class and brown on Bernal. Paraphrasing Alex’s best friend Ben Bac Sierra, if Alex had been white (and not Latino), he would have been approached as an off duty police officer or as the security guard that he was, and an avid 49ers fan, instead of as a gang member implied by the mention of his nice red jacket. Dispatch from that evening reveals police officers hunting him without any intention towards investigation: “He is walking inside the park…” “There’s a guy… way up the hill walking towards you guys…” “I got a guy right here…” “Shots fired! Shots fired!”

The “murder map” created by AEMP shows that 71% of those killed by the SFPD, since 1985, were people of color. Yet perhaps most shocking is that 41% of those killed by the SFPD were black, when only 6% of the population of San Francisco is black according to the 2013 US Census. Racism seems inherent to police shootings everywhere, however, the more subtle connection is about the role police play in protecting private property.

The altar at MCCLA asks the public to express thoughts or comments on the wall by providing two probing questions: “What does (or who do) police protect?” and “How do we end police impunity?” For the first one, a definition of police is also provided:

po•lice /pəˈlēs/ noun

A police force is a constituted body of persons empowered by the state to enforce the law, protect property, and limit civil disorder.[1]

The altar walls continue to shift with the days as public comments are aggregated. A few commentators agree with this definition by pointing out that police protect “themselves” or the “state,” but I’m waiting for the commentator who will hone in on the relevance of having a state armed force with a primary duty to protect property, because by nature of the institution, police end up policing the have-nots versus the haves. Thanks to the residual history of conquest and colonialism the have-nots tend to be people of color, and more generally low-income minorities, who are racially or ethnically discriminated against. Police also exist to protect against civil disorder towards the state, should anyone have the uncomfortable idea that there is a problem with the foundations of a state poised to promote and protect the hierarchies of capitalism.

Our MCCLA altar “Unaccountable Murders” includes a video interview of Mesha Monge-Irizarry, contributed by Ivonne Iriondo. Mesha is the mother of Idriss Stelley, a 23-year-old young man who was killed by nine SFPD officers, when they shot him 48 times at the Metreon in 2001. After the death of her son, Mesha became a ferocious advocate against police brutality, and established the “Idriss Stelley Foundation” in honor of her son. The foundation provides free, confidential services to biological and extended families whose loved ones have been disabled or killed by law enforcement. This is a critical service considering that cities do not acknowledge police shooting victims as victims of crime. While in San Francisco therapy services are offered to any family victimized by a homicide, receiving services from the City that the family will likely fight in a legal case might not be the best environment for recovery. Mesha is a veteran first responder to families facing a crisis over a police brutality incident, and a pain in the ass of SFPD.

All these thoughts loomed large in my mind, as I continued to paint silouhettes of police with weapons drawn on the altar walls, on Columbus Day, in the Mission, which name itself echoes a long history of armed enforcement of outsider claims to land.

Unaccountable Murders, (altar installation), MCCLA, 2014 by Adriana Camarena, Ivonne Iriondo, Erin McElroy

Walls of “Unaccountable Murders” with “Murder Map” by Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, and documentary of Mesha Irizarry by Ivonne Iriondo.

Altar wall as part of “Unaccountable Murders” at MCCLA, 2014 Day of the Dead altars.